But it is the self we are always looking for, or always trying to escape, and fiction provides us with both options; they are wrapped together, these flights to and from who we are. We read because we are looking to see what others are thinking, feeling, seeing; how they are acting out their frustrations, their happiness, their addictions; we see what we can learn.

~~ Elizabeth Strout, Introduction, BASS 2013

I was very enthusiastic about last year’s collection, mostly on the basis of about five stories I found exceptional; there were, of course, a few stories that I found equally, shall we say, unexceptional. I think that range narrowed this year. The highs weren’t as high, perhaps, but neither were the lows as low. It was another good year for BASS.

And a very good year for me: This past summer, I took a MOOC called “The Fiction of Relationship.” It was quite a journey over three centuries, looking at how consistently we create relationships in our heads – relationships with others, with ourselves, with the world. Sometimes the fiction we create of those relationships is shared by others; sometimes, it’s ours alone. Sometimes it helps us deal with the world; sometimes it gets in the way, and sometimes, the relationship we’ve written for ourselves and the world gets in the way of dealing person-to-person.

I see Lambright in “Encounters with Unexpected Animals” as the author of a fictional relationship with Lisa, and I see how she rewrites his fictional understanding completely; likewise Bob and Mr. Wagonseller in “Horned Men.” I think Morehouse in “The Third Dumpster” creates his brother’s relationships with the world for him – and Goodwin would be much better off if he’d create his own. In “Malaria” and “Bravery,” characters develop their relationships over time, changing along the way as they mature and as circumstances change according to the vicissitudes of life. I see the two main characters in “Philanthropy” agree to inhabit one fictional relationship, only to switch roles at the end. It’s a very interesting way to read: the constant evaluation of a character’s construct of a relationship, and of self, carries over to what we euphemistically call “real life,” for it isn’t just characters in stories who create a fiction of their relationships.

One of the surprises of this volume was in the number of stories I’d already read: a total of seven, six from TNY, one from One Story. I didn’t post additional comments on these, though I did re-read them (except for “The Breatharians” in honor of my recently departed Lucy). This was much higher a count than in previous years, even during the year when I read Tin House in addition to those two; the most duplicates I’d encountered before was three. It’s in the good news/bad news department: most of them were stories I’d enjoyed (including a couple of favorites); but, I hate to see one magazine dominate like that, especially one of the major players. One of my favorite aspects of last year’s anthology was the inclusion of a few less well-known magazines new to the series, like Fifth Wednesday and Hobart (which contributed one of my favorites). Be that as it may, this was another excellent year, if a bit less varied and “safer” than last.

My absolute favorites:

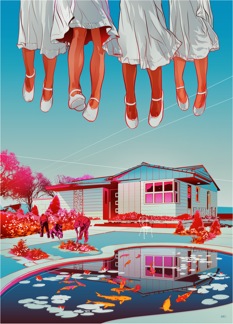

George Saunders, “The Semplica Girls” from TNY

Daniel Alarcón, “The Provincials” from Granta

Alice Munro, “The Train” from Harper’s

Also favorites:

Steve Millhauser, “A Voice in the Night” from TNY

Lorrie Moore, “Referential” from TNY

Bret Anthony Johnson, “Encounters with Unexpected Animals” from Esquire

David Means: “The Chair” from The Paris Review

Suzanne Rivecca, “Philanthropy” from Granta

The one puzzle to me was the inclusion of Junot Diaz’ “Miss Lora” instead of “The Cheater’s Guide to Love” (which is in the “runner-up” list), both from TNY. It’s not I didn’t enjoy “Miss Lora”; it’s just that I loved “Guide” so much.

About a dozen of the “Other Distinguished Stories” – the runners-up – were familiar to me. I was particularly pleased to see “You, on a Good Day” by Alethea Black (One Story); I’m a little surprised the unusual voice didn’t carry the day on that one. Maybe it’s that second-person thing again, or the poetic cadence of the prose – though that didn’t stop them with last year’s “Diem Perdidi”, one of my favorites back then. I have a thing for the offbeat. I also wish humor had been more prevalent. But, while the lyric tone and traditional narrative prevailed (as it usually does) the offbeat made an appearance here as well, with the socially relevant epistolary fantasy “Semplica Girls” and, in a structural sense, “A Voice in the Night”; voices came from across the socioeconomic spectrum, with varied ethnicity and a time span from before the Common Era to fifty years from now.

The other takeaway from my Fiction of Relationship course was the notion of “the law of metamorphosis” – that we can’t truly know another until we become that other. So many characters in the great fiction we read – Melville, Kafka, Coetzee – became the other. Reading fiction is another way to do that – less complete, perhaps, but also less painful. It seems guest editor Elizabeth Strout thinks so, too:

We want to know, I think, what it is like to be another person, because somehow this helps us position our own self in the world What are we without this curiosity Who in the world, and where in the world, and what in the world might we be? So we pay attention to that inner demand, the pressure of that question. Hello? Please – tell me.

~~ Elizabeth Strout, Introduction, BASS 2013

Time to start imagining: what will be included in 2014?

I’d been out of the Conservatory for about a year when my great-uncle Raúl died. We missed the funeral, but my father asked me to drive down the coast with him a few days later, to attend to some of the post-mortem details. The house had to be closed up, signed over to a cousin. There were a few boxes to sift through as well, but no inheritance or anything like that.

I’d been out of the Conservatory for about a year when my great-uncle Raúl died. We missed the funeral, but my father asked me to drive down the coast with him a few days later, to attend to some of the post-mortem details. The house had to be closed up, signed over to a cousin. There were a few boxes to sift through as well, but no inheritance or anything like that.