In this year’s volume of The Best American Short Stories, we are treated to characters like Kavitha, the emotionally numb wife who comes alive only in the face of violence… a desperate absentee father… an emasculated man who sells dental equipment…. a ruthless champion speedboat racer and oil heiress… Here are living, breathing people who screw up terribly and want and need and think uneasy thoughts. Did I like these characters? I very much liked reading tehir stories… I liked the honesty of the portrayals, and their poetry and humor and surprise.

~~ Heidi Pitlor, introduction

I’ve been blogging BASS since 2010, and reading cover-to-cover for two years before that. I’ve noticed a pattern: I tend to like even years better than odd years. I have no idea if that’s coincidence, or if there’s some reason for the oscillation, but being somewhat rational, I suspect the former.

That doesn’t mean I don’t learn something from stories I’m not so crazy about. That’s a good thing, for me, since it serves as a do-it-yourself English class. I think there were more stories I “respected rather than liked” this year than I’ve noticed in other volumes. Perhaps I’m just respecting more as I go along. Or again, coincidence.

I did find two stories I particularly liked: Colum McCann’s “Sh’khol” and Aria Beth Sloss’s “North“. As I read, I was immersed, I wanted to keep reading, and when I got to the end, I felt like I understood something, something important, better than I had before. Because I was immersed, craft took a back seat on first read, but later I noticed some interesting writers’ choices. Since I’ve enumerated what I liked about them in the individual posts, I won’t repeat the litany here.

Then there were the almost-likes, the “I like you but I don’t like-like you.” These are stories that may just grow on me as they tumble around in my subconscious, as other things bring them to mind. The reason I respected them varies. For example:

“Fingerprints” by Justin Bigos came perhaps the closest to being promoted to outright-like. I enjoyed the way the fragments fit together, how the theme of fingerprints carried through, and how all of the characters seemed deeply flawed, but sympathetic instead of blameworthy. However, I realize now, I’ve barely thought about it since reading it.

Julia Elliott’s “Bride” worked for me because of the setting in a medieval scriptorium, the hallucinatory character, and the escalating hilarity.

Ben Fowlkes’ “You’ll Apologize If You Have To” appealed to me for reasons I can’t explain, against all my usual predilections, in fact, but I wasn’t sure of the ending. I’ve already thought of this one a few times in connection with other stories and other events, which is a good sign.

I liked Denis Johnson’s “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden” far more than I’d expected I would (I’ve never read him before; maybe I should start) and I found the individual segments wonderful. I just wonder if it’s a little pretentious. Then again, if you’re Denis Johnson, I guess you’re entitled to some pretension.

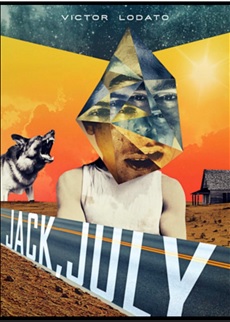

“Jack, July” by Victor Lodato had some wonderful scenes, and I rather liked all the doors, but it still seemed like a lot of sound and fury over a guy who needs to be in a hospital.

“Motherlode” is in this category, even though I truly hated it while reading, because Thomas McGuane’s Contributor Notes made it click. Yes, that’s considered cheating – the story must stand on its own – but once I understood the symbolism, I quite admired how he constructed the story. But I really don’t want to read it again.

I felt similarly about Maile Meloy’s “Madame Lazarus” – the idea that she was thinking of collaborators and resistors in postwar France amazed me – but I enjoyed the story much more, simply because I’m a complete sucker for a dead pet story. And for exactly that reason, I demand it do more. It did, but I didn’t see it. My failing, as with McGuane? Sure, I’ll take the hit. But still, the fact remains: I didn’t get it, so I can’t really claim it to have liked it on its own terms.

Then there was a trio of WTF stories – there always are – but I won’t list them. Again, I’ll take the hit for not seeing the brilliance there. Maybe it’s a different-wavelength thing, or personal taste, whatever.

One pleasant surprise for this year’s reading was the consistent presence of another reader, leaving comments on each story. I greatly enjoyed trading what we liked and disliked, and what stood out for each of us; whether we agreed or disagreed, I learned from each comment. In a world (and a social media environment) – where the New York Times just declared “Obnoxiousness is the new charisma” – a world more and more conflict-driven, where even trivial discussion becomes an argument and winning is the goal, it’s great to find a place where the genuine exchange of ideas can take place.

Exit BASS – pursued by Pushcart XL.

This was her flaw as a parent, she thought later: she had never truly gotten rid of the single maternal worry. They were all in the closet, with the minuscule footed pajamas and the hand-knit baby hats, and every day Laura took them out, unfolded them, try to put them to use. Kit was seven, Helen nearly a teenager, and a small, choke-worthy item on the floor still dropped Laura, scrambling, to her knees. She could not bear to see her girls on their bicycles, both the cycling and the cycling away.… Would they even remember her cell-phone number, if they and their phones were lost separately? Did anyone memorize numbers anymore? The electrical outlets were still dammed with plastic, in case someone got a notion to jab at one with a fork.

This was her flaw as a parent, she thought later: she had never truly gotten rid of the single maternal worry. They were all in the closet, with the minuscule footed pajamas and the hand-knit baby hats, and every day Laura took them out, unfolded them, try to put them to use. Kit was seven, Helen nearly a teenager, and a small, choke-worthy item on the floor still dropped Laura, scrambling, to her knees. She could not bear to see her girls on their bicycles, both the cycling and the cycling away.… Would they even remember her cell-phone number, if they and their phones were lost separately? Did anyone memorize numbers anymore? The electrical outlets were still dammed with plastic, in case someone got a notion to jab at one with a fork.